Yesterday I was on the phone with a customer service representative at Bank of America. The account I keep for my son had received a $40 overdraft charge because his SSI payment hadn’t auto-deposited in time for his rent check. Because of the government shut-down. Because he is on disability. Because he couldn’t possibly hold a job. Because he has schizophrenia. Because.

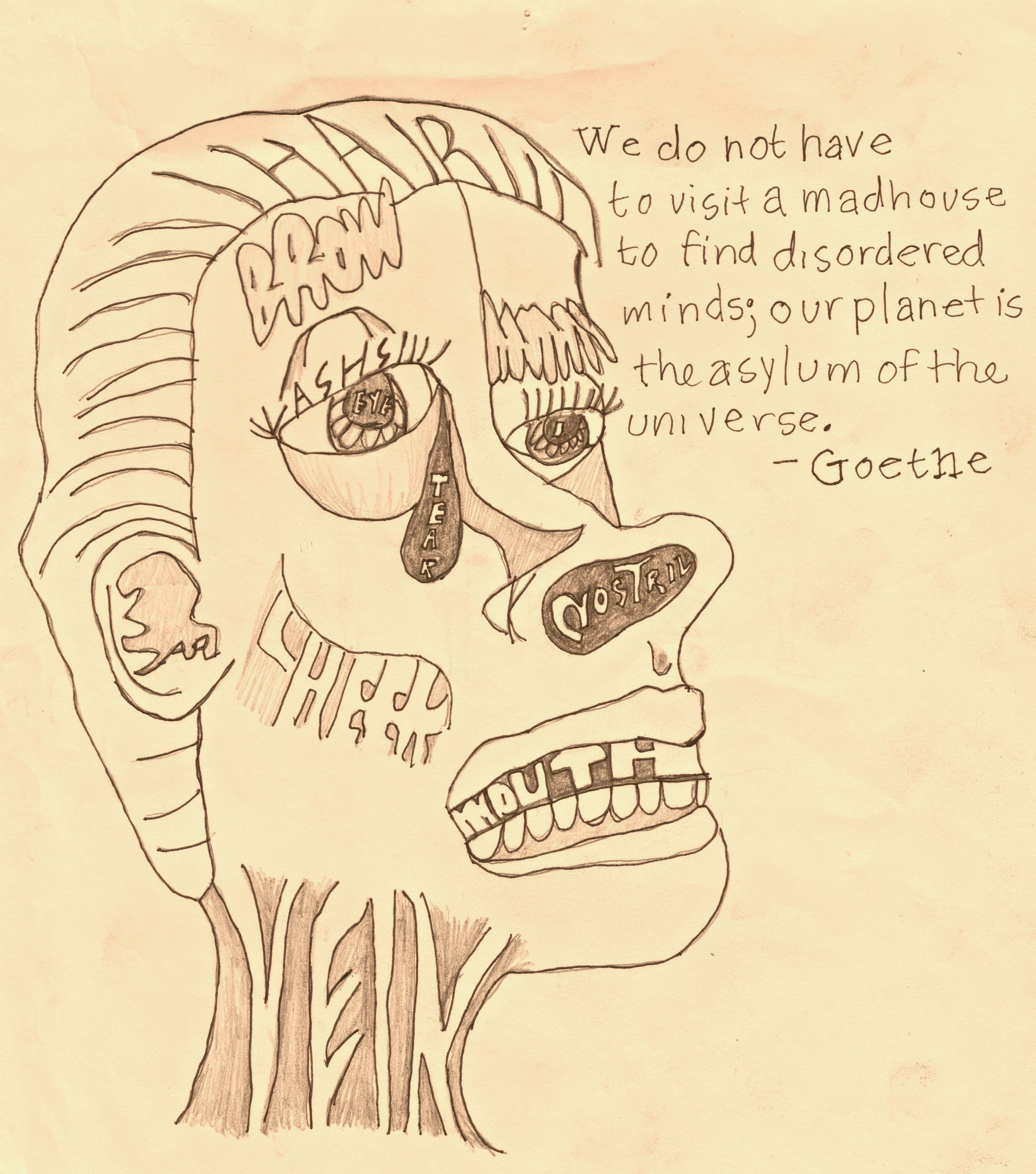

I was talking to a therapist recently who told me that schizophrenia is the black sheep of mental illness. I already knew that. It isn’t understandable like bipolar. It isn’t treatable like depression. It isn’t recognizable like anxiety. In a world of strangeness, it is the strangest of all. It renders its sufferers sick by attacking the very organ that would allow them to understand and seek treatment, the mind. It is a thought disorder. Think about that (ha. yes, think) and imagine someone you love becoming another person. Receding and transforming and returning in an unrecognizable form. There is a particular irony to this disease, it has a cruel joke quality.

I am very open about the situation. I decided a long time ago that I didn’t have the energy for the tap dancing that bowing to stigma requires. This wasn’t a bold or noble move on my part. It was the need for efficiency. The stress and maintenance of this circus requires everything I’ve got. Superfluous activity and emotions are discarded.

I explained to the bank lady what had happened. I could have said “my son is on disability” but that is vague and sanitized. I prefer sharpening the pencil more than that. Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “words are deeds.” God, I remember that from art school, it put a fine point on my attitude about art, about words, that has stayed with throughout my life. I believe that being sloppy with words leads to calamity. Misunderstanding. Tragedy. So, I say “my son has schizophrenia.” I need this to be exactly the thing that it is.

There is a slight pause and then she kindly, politely, removes the charge from his account. At the end of the conversation, at the place where she is supposed to say is there anything else I can help you with she instead says you know I have a family member dealing with this, it is my father. I say something affirming, give her the verbal secret handshake, and we talk for a few more minutes. I listen to her story. We don’t care if this conversation may be recorded for quality assurance. We are in the trenches.

Later that morning, on the phone with the dentist’s office, the same thing happens again. When I tell the receptionist that they need to be aware of Nick’s condition, she tells me all about her brother. It dawns on me: people are dying to talk about it.

In the sliver of space between can I help you and thank you for calling, they want to talk about it. In the tapered silence after do you want a receipt with that, they need to tell someone their story. Wait before you say good night, your own child may have something they desperately need to tell you.

People are afraid to open up about mental illness, but at the same time they are dying to talk about it.

Let’s start listening.